Where Autonomy Works: Evaluating Robot Capabilities in 2026

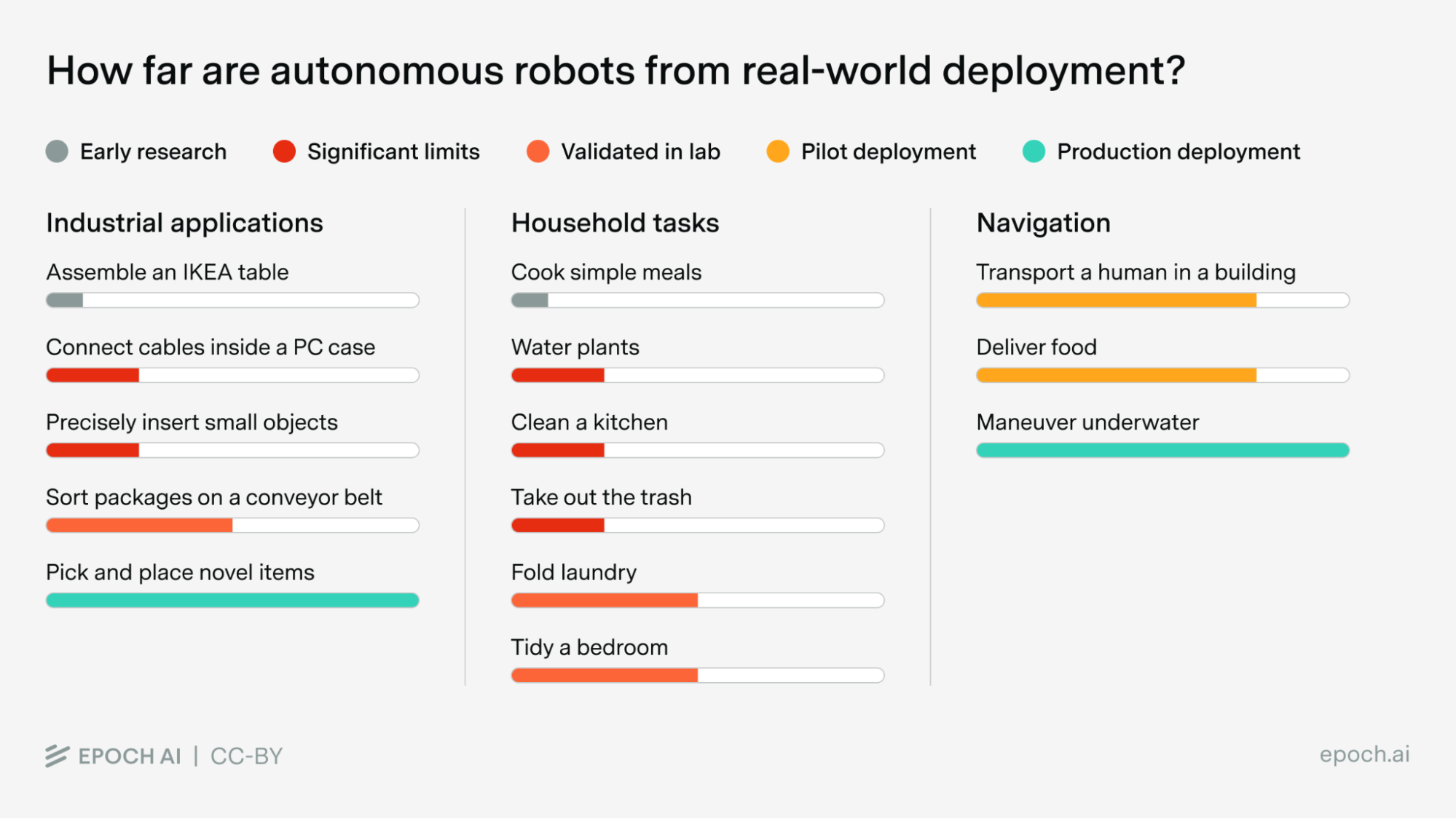

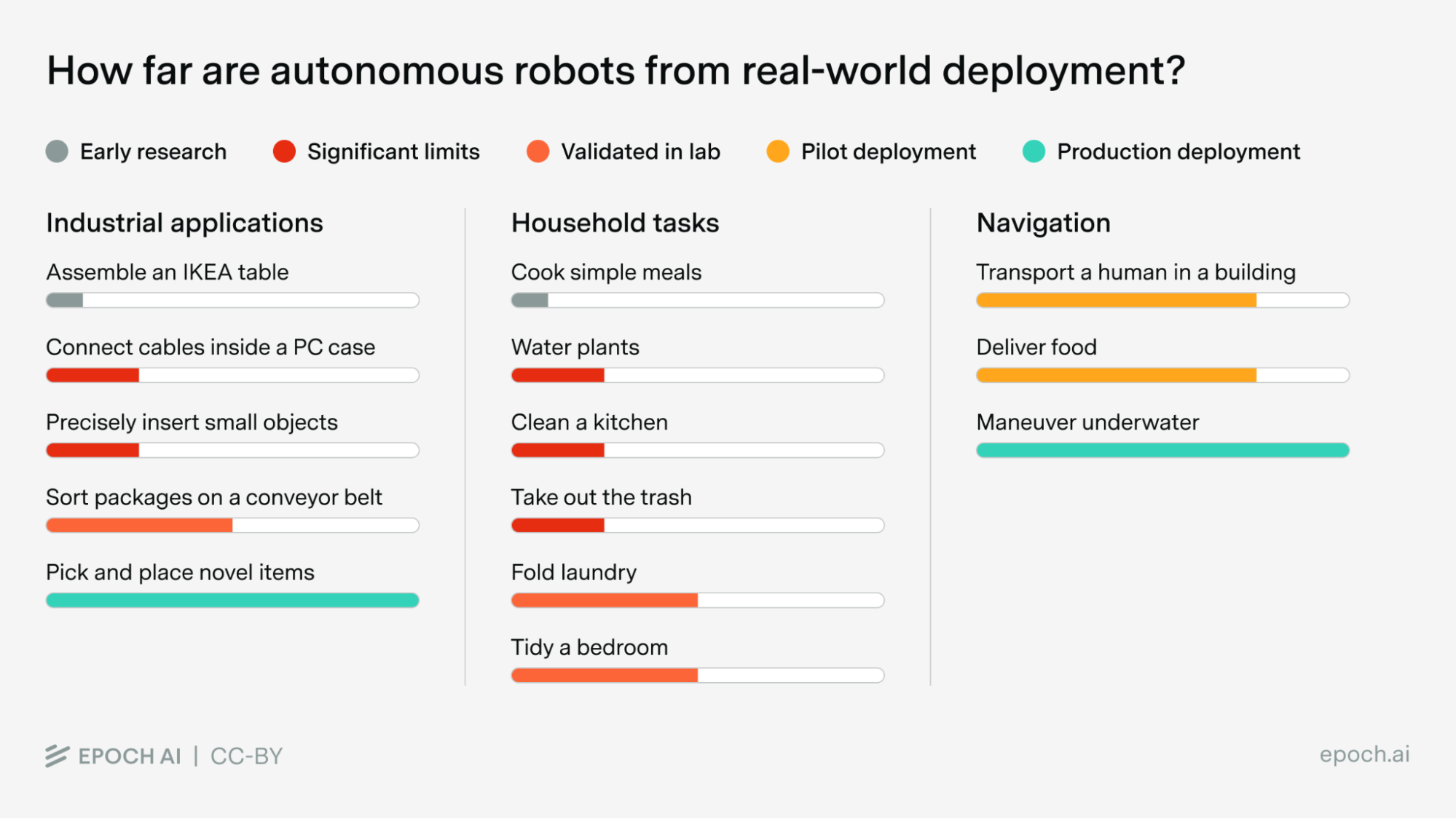

We assess the current state of autonomous robotics by evaluating robot performance on concrete tasks across industrial, household, and navigation domains.

Published

Introduction

Impressive demos are not hard to come by in autonomous robotics. Forming a precise understanding of real-world capabilities is much harder: a task that looks solved in a demonstration may be brittle in deployment. This report assesses robot performance on concrete tasks across three domains (industrial, household, and navigation). For each task, we review the available evidence on reliability, speed, cost, and the ability to adapt (“transfer”) to new environments and objects.

Key takeaways

- Navigation is deployed commercially, while most industrial and household tasks are not. Autonomous robots already deliver food in multiple cities, transport goods in warehouses, and inspect infrastructure in remote environments with high reliability. Most tasks requiring robots to handle, assemble, or manipulate objects remain largely in the lab.

- Manipulation is commercially deployed in controlled environments with simple tasks, but mostly not beyond. Warehouse picking is the clearest example: robots can handle thousands of object types reliably, because the environment is stable, can be designed around the robot, and the task itself is straightforward. The further we move from that (to more complex multi-step tasks, or more variable environments like homes), the less reliable things get.

- Transfer is rarely demonstrated, and matters for most applications. For robots to be useful beyond narrow, pre-defined tasks, they need to handle new objects, new environments, and new tasks without extensive retraining. This is the main bottleneck: most demonstrations show robots fine-tuned on specific tasks in specific settings. Unless transfer is explicitly shown, it should not be assumed.

- Speed is not solved, but is not the main bottleneck to deployment. Robots are typically 3–10× slower than humans. But a robot working 20 hours a day compensates for being slower per task, and in household contexts, a robot working while the user is away could be five times slower without losing its value.

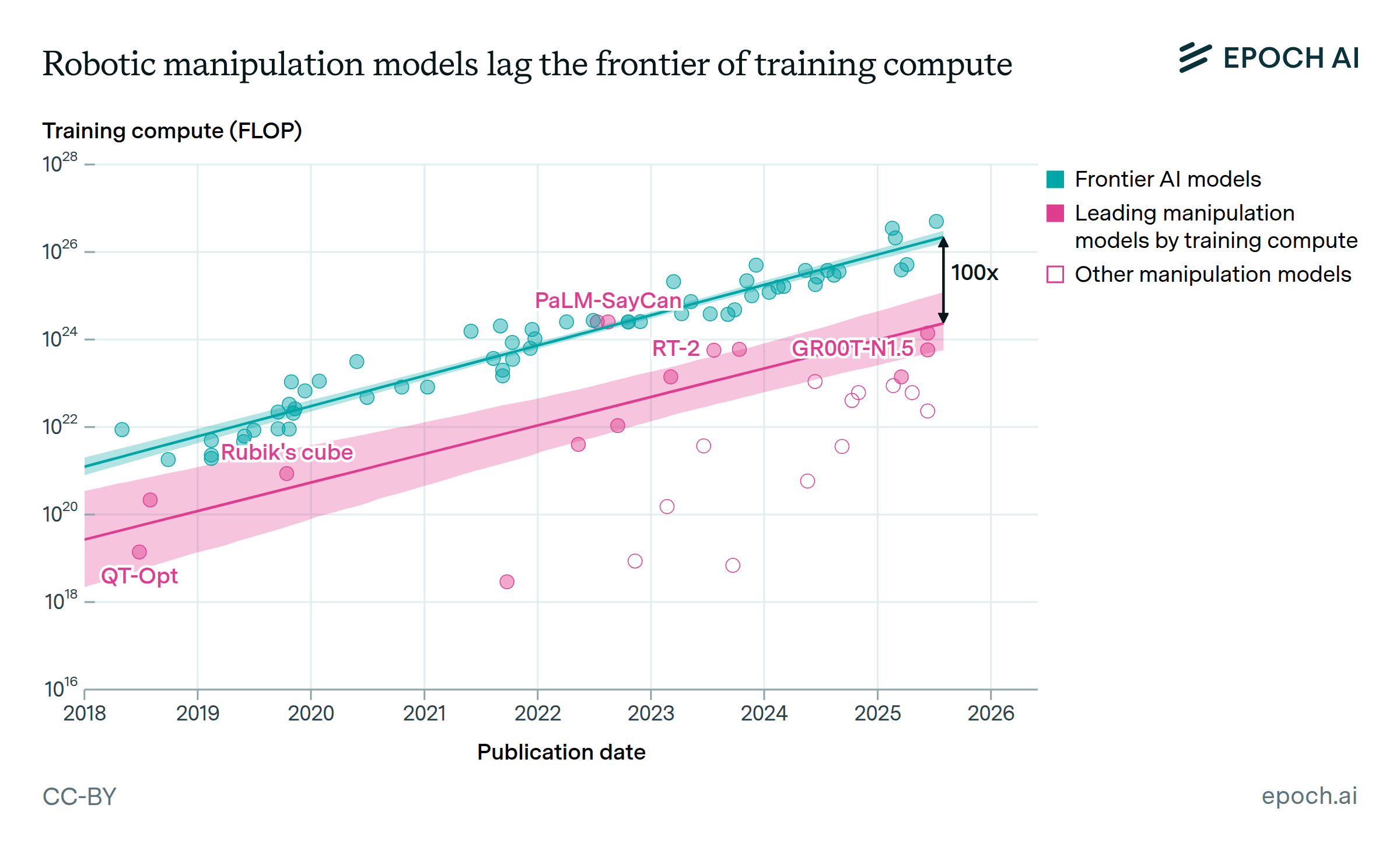

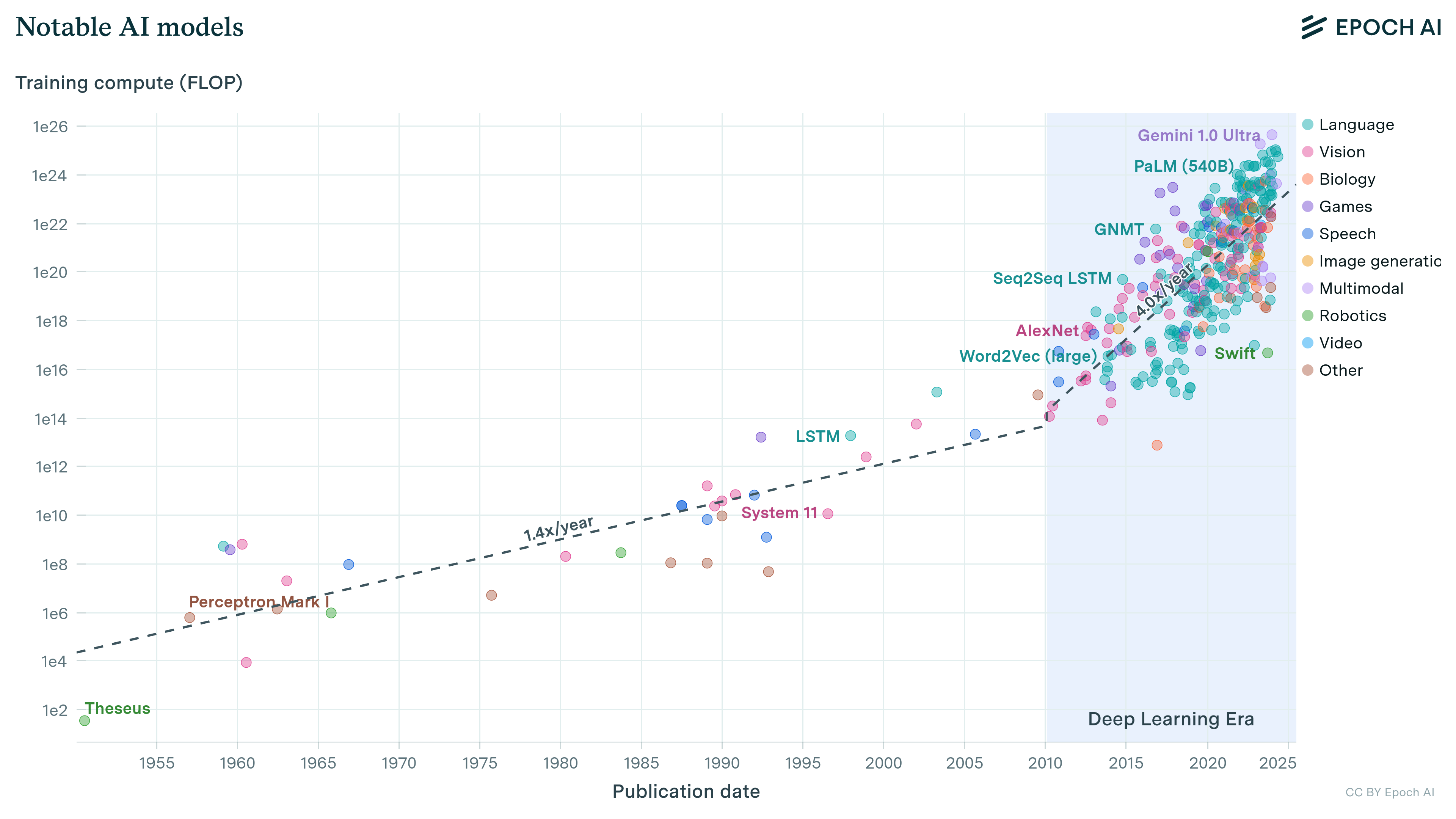

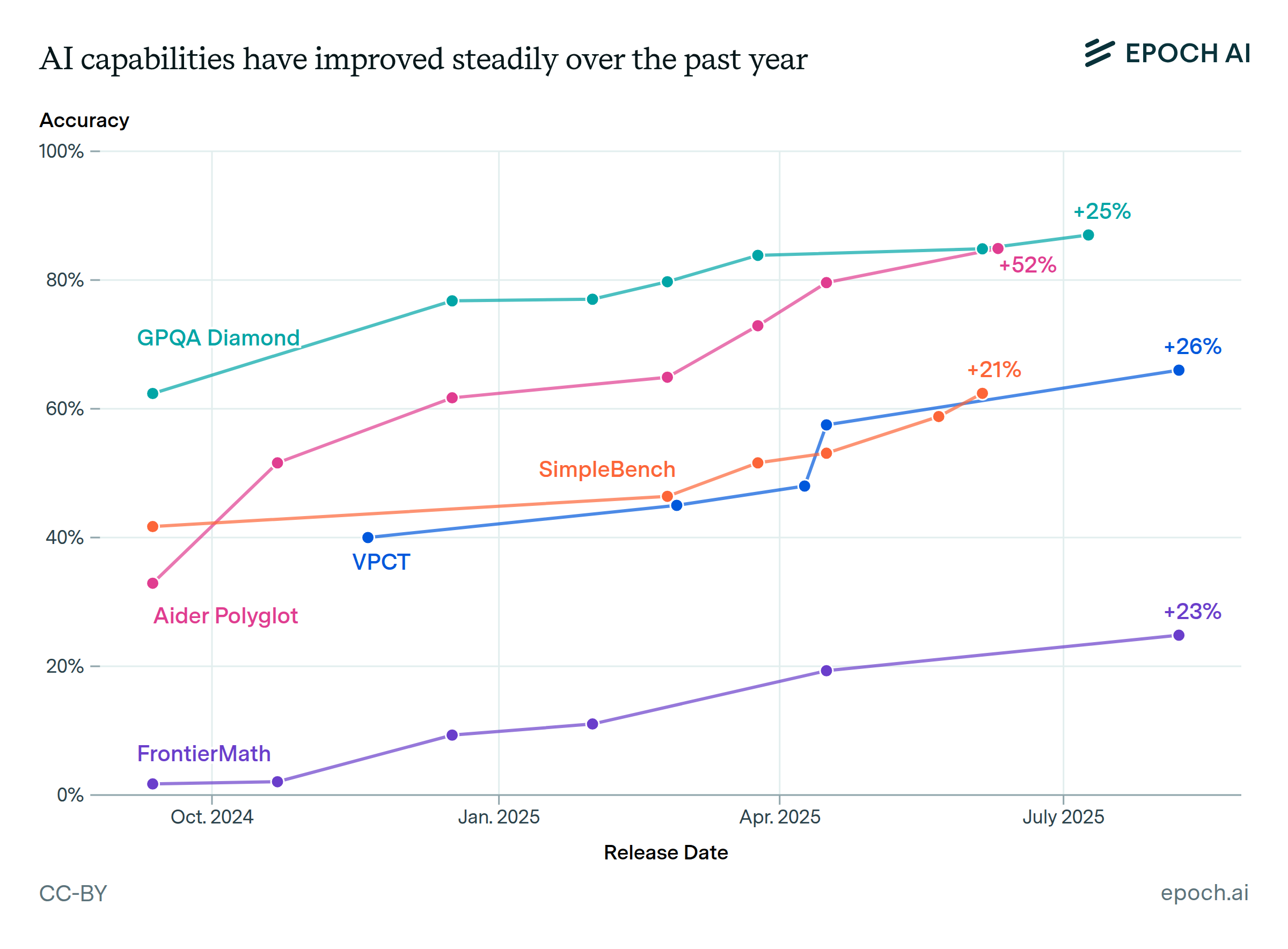

Foundation models have become the default for robot manipulation

Most of the manipulation results in this report come from robot foundation models: systems that leverage large-scale pretraining before being adapted to specific tasks. These take different forms: vision-language-action models that build on pretrained vision-language models (Physical Intelligence, Figure, Google DeepMind), world models that derive actions from pretrained video generation (1X), systems pretrained on massive-scale simulations across many robot form factors (SkildAI), and models pretrained on large corpora of real-world robot interaction data (Generalist AI). Despite their differences, all of these approaches make a similar bet: that broad pretraining produces better robots than training from scratch on each task.

In language modeling, there was a crossover point last decade where fine-tuning a pretrained model became better than training a task-specific model from scratch. Early evidence suggests this crossover is happening for robot manipulation. The strongest signal is that every leading company tackling the hardest tasks in this report (household and complex industrial tasks) employs a pretrained foundation model rather than training from scratch. For example, the Toyota Research Institute compared a fine-tuned pretrained model against single-task specialists across 1,800 real-world and 47,000 simulation rollouts, and found that the pretrained model matched or outperformed specialists on nearly all tasks.

To reach the best performance on the harder tasks covered in this report, foundation models are still fine-tuned on task-specific data. And those tasks are not yet reliable enough for widespread commercial deployment regardless of approach. The tasks that are commercially deployed (warehouse picking, delivery, underwater navigation) are simpler ones where purpose-built systems already work well.

Separately, off-the-shelf language and vision models like Gemini 3 Pro and Grok 4 will play a growing role in the cognitive components of robot tasks: understanding what needs to be done, deciding where objects belong, or tracking progress through a multi-step plan. For example, Figure has integrated the OpenAI API into their robots for this purpose, and Elon Musk recently described Grok as the future orchestration layer for Tesla’s Optimus robots.

Methodology

This report assesses the current capabilities of autonomous robots: systems that can perceive their environment, make decisions, and act without human control. This excludes the large majority of deployed industrial robots today, which follow scripted or teleoperated routines. Our analysis is form-factor agnostic: for each task, we assess whichever robot performs best, regardless of whether it is a humanoid, a robotic arm, a wheeled platform, or a drone.

To assess where autonomous robots stand, we selected concrete tasks across three domains (industrial, household, and navigation) and evaluated how well robots can perform each one. We chose tasks based on economic relevance, whether the underlying skills would transfer to other applications, and whether enough demonstrations or deployments exist to make an assessment possible.

For each task, we assess reliability (success rate and failure modes), speed relative to a human, cost and operational constraints, and transfer to new environments and objects. In some cases, data on one or more of these dimensions is limited, but we generally have enough to form a picture.

We classify each task into one of five categories:

- Early research stage: Only fragments of the task have been demonstrated, with core capabilities remaining unproven even in controlled settings.

- Significant limits in lab: Individual skills have been shown but with severe constraints. Not close to real-world viability.

- Validated in lab: Most required capabilities demonstrated in controlled environments with reasonable reliability. Real-world deployment could be considered.

- Pilot deployment: Real-world deployments in limited geographic or operational scope.

- Production deployment: Proven economic value, meeting domain safety and quality thresholds, with commercial deployment.

1. Industrial applications

Non-autonomous automation has already transformed sectors like automotive manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, and food processing. But current industrial robots are narrow: a FANUC arm welds the same joint on a car frame thousands of times; a pick-and-place robot in a pharmaceutical plant moves vials between fixed positions. Each is programmed for a specific task in a controlled environment.

Robots that can handle varied tasks, move freely around a facility, and work alongside humans would significantly expand the market for industrial automation: robots can work continuously without breaks, do not need lighting or climate control, and can operate in environments unsafe for humans. An early example of this is Staples Canada, which removed conveyors in favor of robots in its largest fulfillment center outside Toronto, responsible for nearly 50% of its national e-commerce volume.

Warehousing and logistics represent a large near-term opportunity. The warehouse robotics market is currently around $10–15 billion and growing 15–20% annually.1 Amazon has deployed over a million robotic units across its facilities, though most have limited autonomy.

Manufacturing and assembly is a larger but more mature market. The industrial robotics market overall represents about $40 billion2, and is dominated by automotive and electronics. Most current deployments are fixed-position robots doing repetitive tasks like welding and component placement.

The value of more autonomous robots here is less clear than it might seem. One view is that manufacturing has already been divided into (a) specialized tasks handled by narrow automation and (b) cognitive tasks for humans, with relatively few manual dexterity bottlenecks remaining. On this view, improvements to robot dexterity would be nice-to-have but not transformative. The counterargument is that cost savings and more general robots could open automation to smaller operations that cannot justify custom assembly lines, and that it is hard to predict what becomes possible in a very different capability regime.

Construction is harder but potentially transformative. Labor shortages are acute (the US faces a deficit of hundreds of thousands of skilled workers) and productivity growth has been notoriously low. But construction sites are unstructured and constantly changing, making autonomy much harder than in warehouses. Current deployments are mostly specialized robots handling individual steps like demolition, bricklaying, and surveying. Even fully automating these individual steps would represent major progress in an industry where productivity has barely grown in decades.

Tasks we assess

We assess five tasks in two categories. The first three tasks assess capabilities that matter for manufacturing but also transfer more broadly. We look at cable insertion, which we operationalize as connecting cables inside a PC case where space is tight and visibility limited. We also study robots’ ability to assemble IKEA furniture, which requires multi-step planning, bimanual coordination, and tool use. Finally, we assess whether robots can insert small objects like keys or earphones into receptacles with high precision.

Next, we turn to logistics tasks (sorting packages and picking items of varying fragility and weight), which represent the largest near-term market and already see some commercial deployment. These test a robot’s ability to adapt grip strength, discriminate among object types, and handle both heavy and delicate objects.

Industrial applications: Takeaways

- Autonomous industrial robots remain a small fraction of deployed industrial robots. They are also more specialized compared to household applications: the humanoid form factor is rarely the best suited for the job.

- Warehouse and logistics are the clearest near-term path for higher autonomy, as most of the low-hanging fruit involves variations of picking and moving items. Assembly tasks remain hard due to the need for precision and multi-step planning.

- Capabilities for small objects and high-precision tasks remain narrow. Demonstrations show individually impressive skills (using keys, inserting airpods) that would be valuable if they transferred to new objects and contexts. But without transfer, each demo remains a one-off, and purpose-built non-autonomous automation will outperform a robot trained on a single task.

- Transfer remains limited and rarely measured. Many demonstrations appear to depend on controlled setups, narrow object distributions, and heavy resets. Reviewers should not infer out-of-distribution robustness from demos unless explicitly tested. Lack of transfer is acceptable for some warehouses and factories, where the environment can be designed around the robots. It does not extend to construction sites or other settings that are inherently unstructured and constantly changing.

1. Connect cables inside a PC case

Significant limits in lab

Task description: The task is to autonomously insert cables into their corresponding ports. We operationalize this as assembling a PC: connecting at least three types of cables (a SATA cable, a power supply cable, and an external cable like HDMI or USB) inside a standard desktop computer case with components already mounted. Once done, the computer must boot and function normally. We chose this operationalization because it requires working in a constrained space with limited visibility, which is representative of many real-world cable assembly tasks.

Current capabilities: No robot has attempted the full PC assembly task. However, there has been progress on the underlying capability of cable insertion in more accessible settings:

Gemini Robotics 1.5 inserted and removed power, USB, and LAN cables from a computer’s front panel. A recent paper achieved 100% success inserting four types of connectors (USB stick, HDMI, DisplayPort, Type-C), though still very slowly (27 seconds per insertion). However, this involves rigid connectors, which are easier to handle than flexible cables.

Separately, CATL has deployed humanoid robots to insert connectors into battery packs, claiming 99% reliability and human speed. This is notable because the connectors are attached to flexible cables that can twist and sag, which is notoriously difficult for robots to handle.

These demos operate on external, easily accessible ports. The harder problem is working inside a cramped PC case, where visibility is limited, the robot’s form factor must fit, and cables need to be routed through narrow spaces. This gap is why we classify the task as “Significant limits in lab” despite the encouraging demonstration results.3

2. Assemble IKEA furniture

Early research stage

Task description: The task is to autonomously assemble a piece of IKEA furniture comparable to the NORDKISA dressing table, within four times the speed of an average human. The robot should not have been trained on the specific model it builds, and the result should be structurally sound for normal use.

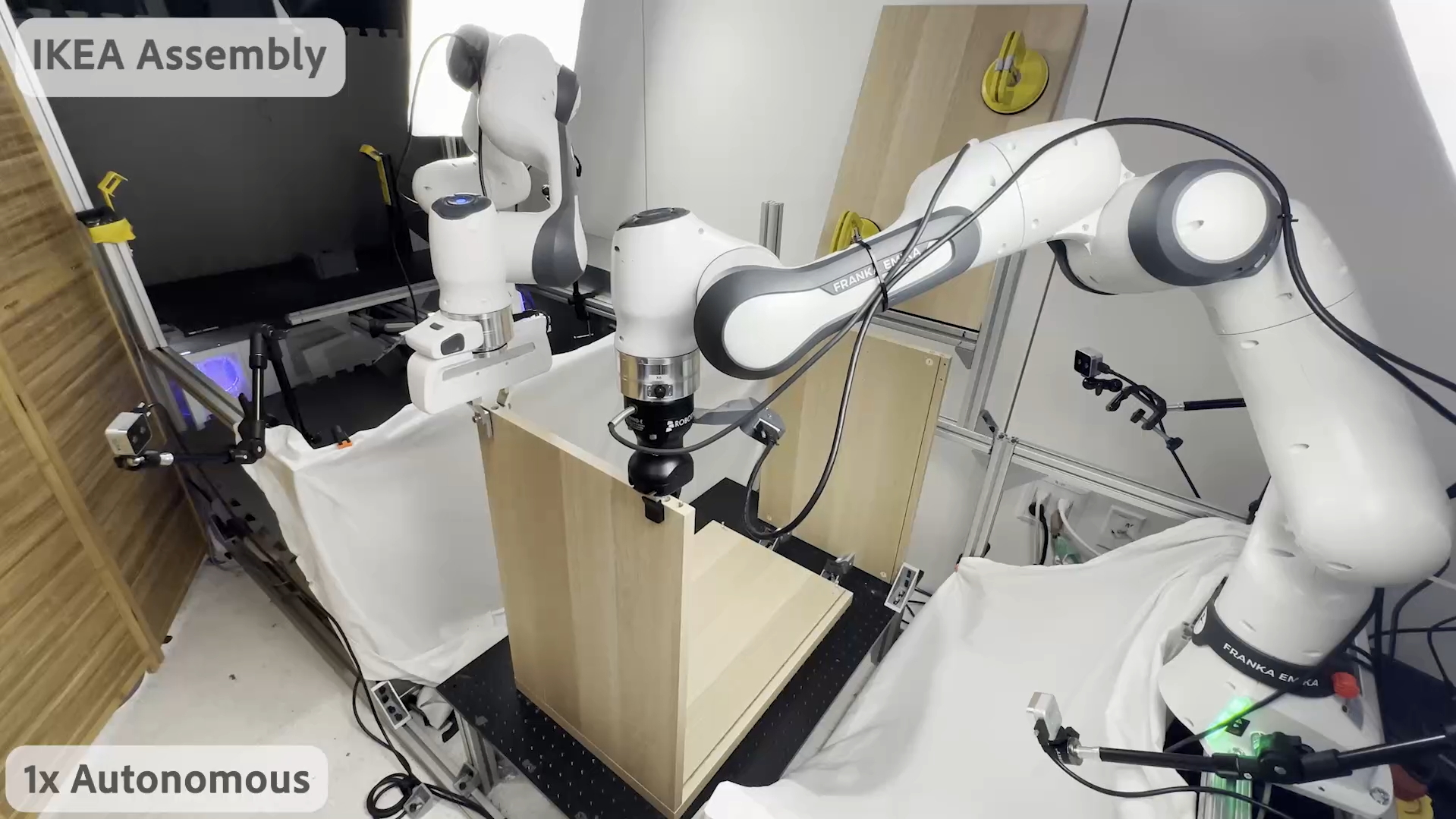

Current capabilities: This task remains far from solved. The closest demonstration is a Berkeley robot (see image below) that handles planks and positions them precisely for screwing. This is a small fraction of the abilities required for furniture assembly, which also involves using tools, handling varied parts, and executing multi-step plans.

Moreover, even this robot has severe limitations. It only handles one type of wooden plank, not screws, brackets, or parts of different shapes. A human performs all the actual screwing. The final plank uses purpose-built handles, which suggests that the robot’s grasping capabilities are limited and required a workaround. There is no demonstration of transfer to other furniture.

We classify this as “Early research stage” because only fragments of the task have been demonstrated and core capabilities (using tools, handling varied parts) remain unproven.

3. Insert small objects with high precision

Significant limits in lab

Task description: The task is to autonomously pick a small object like a key, a straw, or a card, and insert it into a receptacle. The receptacle may be asymmetric, requiring the robot to orient the object correctly before insertion. All items must be novel instances from the same object categories as those in the training data (e.g., different types of keys, not the same key-lockbox pair).

Current capabilities: Several robots have demonstrated high precision insertion, though all with significant limitations:

SkildAI demonstrated a robot inserting airpods into their charging case. This requires orienting the earphones correctly (both top/bottom and left/right). The magnets inside likely help, but the demo shows the robot correcting misaligned airpods on its own. SkildAI’s robot appears at least three times slower than a human, but the variably sped-up video makes this hard to assess. There was no demonstration of transfer to other items or locations.

Physical Intelligence demonstrated a robot using a key in two contexts: a lockbox and a door. The robot inserts and turns the key to unlock. The author of the Robot Olympics challenge noted that key insertion and turning is “a crazy hard precision skill especially without any force sensing.” The robot is about 5× slower than a human. There is no demonstration of transfer to other locks or doors, and in the demos, the robot orients the key correctly without looking at the keyhole, suggesting it was trained specifically on these locks (PI reports collecting under nine hours of task-specific data for most of their Olympic tasks). Reliability across PI’s Olympic tasks averaged around 52%.

DeepMind demonstrated a robot lacing shoes about four times slower than a human4. Since the robot only handled laces, which have consistent shape, transfer to other shoes could be feasible, though this was not demonstrated. ByteDance’s GR-RL can insert laces through eyelets with 83% success rate, about five times slower than a human, with no demonstration of transfer.5

We classify this as “Significant limits in lab” because while high precision insertion has been demonstrated across several tasks, robots are typically 3–5× slower than humans, reliability is often low or unclear, and demonstrations do not show transfer to new objects or contexts. Unlike warehouse picking where narrow task-specific robots can have clear commercial value, it is hard to identify useful applications for these specific tasks (inserting airpods, using keys) that would not require transfer to new objects or environments.

4. Sort and handle packages on a conveyor belt

Validated in lab

Task description: The task is to discriminate among items, perform package-specific operations (rotating, spreading, etc.), and move them between conveyor belts in a warehouse setting. The robot must adapt to different package types (carton boxes, jiffy mailers, polybags). Overall performance should be good enough to substitute for a human worker at that position.

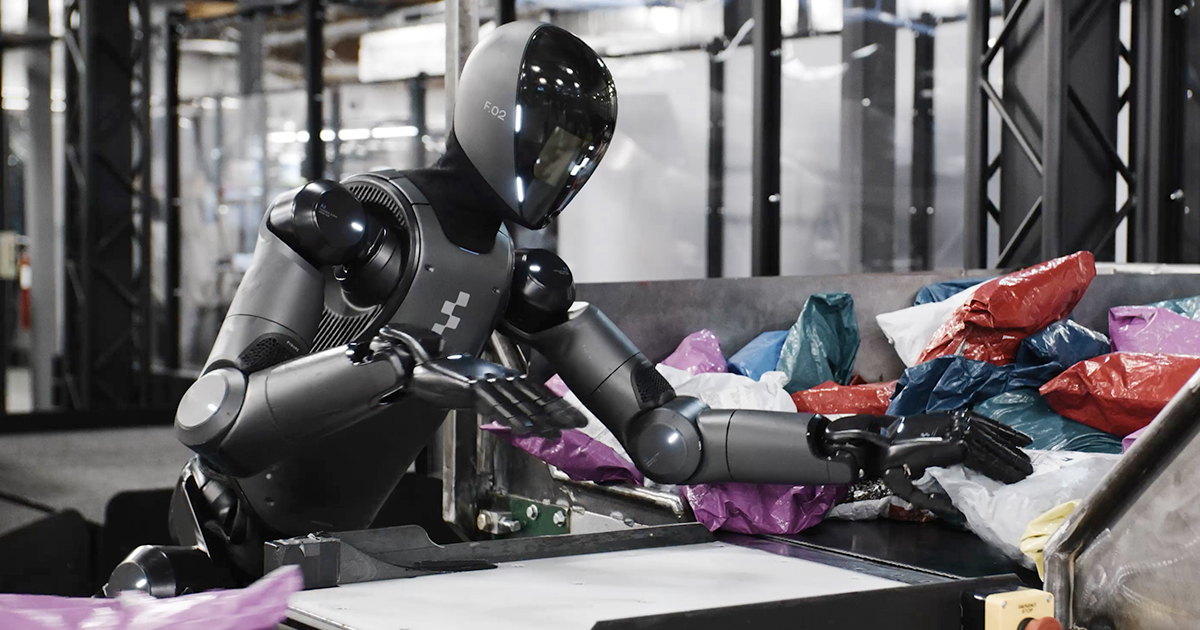

Current capabilities: Figure demonstrated a humanoid robot performing this task with a claimed 95% accuracy in a one-hour uncut demo (see image below), which is notable since most robotics demonstrations are short, heavily edited clips. The robot discriminates between plastic packages and cardboard boxes: it handles cardboard quickly and roughly, while moving plastic packages more gently and spreading them to make barcodes scannable. It rotates packages to expose barcodes and moves items between conveyor belts.

Speed remains far from human: over the hour-long demo, the robot was roughly four times slower than an average worker. Reliability in this limited setting was over 95%: the robot occasionally struggled but recovered without prolonged failures. There was no demonstration of transfer to other package types or sizes.

We classify this as “Validated in lab” because, to our knowledge, it has not seen real-world deployment. However, the demonstrated capabilities and reliability appear sufficient for deployment in real-world contexts, even if initially with limited scope.

5. Pick and place items of varying fragility and weight

Production deployment

Task description: The task is to autonomously pick objects across a wide range of fragility and weight and move them to a new container or conveyor with over 99% reliability. Items can be soft, rigid, or flexible, and the robot must adapt its grip to avoid damage. For instance, a cardboard box must not be handled the same way as a bag of potato chips.

Current capabilities: There is at least one real-world deployment of a robot able to do this task: Amazon’s Vulcan (see image below) is a fixed robotic arm that picks items from storage pods and stows them into compartments, handling a wide variety of objects from rigid items like books or bottles to fragile ones where grip control is essential, like a bag of Skittles. Vulcan’s speed is close to human on each operation, which means faster over longer periods since the robot does not need breaks. In the rare cases where the robot cannot handle an item, it calls for human intervention. Vulcan’s main limitations are that it operates in a humanless zone and has very limited mobility, as its hardware restricts it to very limited horizontal and vertical movements.

There is also a notable robot able to handle heavy boxes that vary in weight: Boston Dynamics Stretch (estimated $300,000–500,000) unloads containers with heavy cardboard boxes in real deployments like GAP warehouses, (see image below) taking boxes from containers to conveyor belts at speeds that appear faster than humans. The main limitation is that Stretch is only autonomous while unloading—an employee must bring it to the right location.

Based on interviews with roboticists, reliability in such warehouse deployments is over 99%, possibly 99.9%.

We classify this as “Production deployment” because these robots are operating in real warehouses among humans with proven economic value. Even if Vulcan was still officially in a beta phase a year ago, Stretch is fully commercially available.

2. Household

Cleaning and lawn mower robots are already a $10 billion combined market, expected to double in the next five years. These robots have become ubiquitous despite limited and narrow capabilities, which suggests strong consumer demand for robots that could handle repetitive household tasks.

If a general-purpose robot could autonomously handle laundry folding and cleaning duties (the two most requested features according to surveys) with greater than 90% reliability, this would open up a large consumer market even at price points of around $20,0006. Similar capabilities would also be valuable in commercial settings like cleaning hotels and office buildings. Robot-as-a-Service models could make this more accessible by handling maintenance and repairs rather than requiring customers to manage these themselves.

Household robots have fundamentally different success criteria from enterprise robotics. Speed and per-task reliability matter less than range of capabilities and robustness. A factory can be designed around its robots and keeps its environment stable; a home is constantly changing. A user would not want to retrain their robot whenever they buy new pots and pans, get a different duvet, or rearrange furniture. This makes generalization to novel objects and configurations the key bottleneck for household robotics in a way that is not true for industrial applications.

Tasks we assess

We selected six tasks. Laundry folding and kitchen cleaning are the top two consumer requests. Together, our tasks test the core capabilities a household robot would need: manipulating deformable (laundry, trash bags) and rigid (dishes, tidying) objects, using tools (cleaning supplies, watering cans), integrating navigation and manipulation (taking out trash), and executing multi-step tasks under time pressure (cooking, kitchen cleaning).

Household tasks: Takeaways

- Laundry folding and tidying are closest to real-world deployment; the remaining tasks are not. Both have demonstrated reasonable reliability and transfer to new homes and objects. For the other four tasks, robots are either unreliable on some subtasks (kitchen cleaning, plant watering), have only shown fragments of the full task (cooking), or have core components that remain unattempted (closing and carrying a trash bag end-to-end).

- Transfer remains largely undemonstrated. The two most advanced tasks, laundry and tidying, are exceptions: PI’s models generalize to unseen homes and novel objects. For the remaining tasks, transfer is essentially untested. And even for laundry and tidying, the harder transfer problems remain open: adapting to new appliance interfaces, and handling unexpected object states (a nearly-full vs. nearly-empty dishwasher, dried vs. fresh food residue).

- Cooking has the widest gap between demonstrations and the full task. Individual skills exist (grilling meat, making a sandwich), but no robot has attempted complete recipes like pasta or salad, and none has demonstrated learning new recipes by building on previously acquired skills. Cooking is also particularly hard: timing constraints make errors unrecoverable, kitchens vary enormously, and worst-case failures carry real risk.

- Robots are two to ten times slower than humans, but for most household tasks this matters less than it seems. Users can leave the robot working while doing something else, so a robot that takes 30 minutes to fold laundry still saves the user’s time.

1. Cook simple meals

Early research stage

Task description: The task is for a robot to cook a simple sandwich like a BLT, a pasta dish, and a salad. Ingredient preparation (chopping, peeling) is in scope, but the robot may use standard kitchen appliances.

Beyond executing these specific recipes, the robot should be able to learn new simple recipes within the same categories from a small number of demonstrations (under ten). For example, a robot that can make a BLT and a club sandwich zero-shot should be able to learn to make a PB\&J from a few demos. A robot trained on spaghetti bolognese should quickly learn to make pasta carbonara.

The result does not need to be as reliable as an average human, but should meet a reasonable standard: for instance, pasta should not be badly overcooked, and dropping ingredients should be minimal.

Current capabilities: Several robots have demonstrated individual cooking skills. Zippy (see image above) is used by chefs, including a two-star Michelin chef, to cook meat on a plancha. It adapts its behavior to the type of ingredient in a pan or pot and can use specialized cooking hardware like a flat-top griddle or a tilting skillet. Other robots have demonstrated making a peanut butter sandwich, making an omelet, and cooking shrimp in a pan.

However, these demonstrations fall far short of the task as we defined it above. Many basic cooking skills remain unattempted: no robot has made pasta or a salad (aside from specialized robots like Thermomix). Even the most capable systems require significant human intervention: in the Zippy demonstrations, the ingredients have already been peeled and cut by humans. Most critically, no robot has demonstrated learning new recipes from a small number of demonstrations while building on previously acquired cooking skills. Each demo represents a narrow, trained behavior rather than evidence of generalizable cooking capability.

Speed is already sufficient: the sandwich was made 2.5× slower than a human, and Zippy operates at roughly 60% human speed. Reliability is unclear for most systems.

We classify this as “Early research stage” rather than “Significant limits in lab”. The comparison to IKEA furniture assembly is instructive: both tasks have seen only fragments demonstrated, with core requirements unproven. More cooking demos exist than furniture assembly demos, but the cooking task as defined sets a harder bar. IKEA assembly requires executing a multi-step plan with varied parts; cooking as defined here requires that plus the ability to generalize across recipes from a few examples. No current system has attempted this transfer requirement, let alone achieved it.

2. Water plants

Significant limits in lab

Task description: The task is to autonomously water household plants using ordinary tools like a watering can. The robot may be told how much water each plant needs, but must generalize to plants and pots of different shapes and sizes, not just those seen in training. Minor spillage is tolerated but the robot should avoid pouring water on leaves or furniture.

Current capabilities: Several companies have demonstrated plant watering, but all with significant limitations.

MindOn, a Chinese company, showed a Unitree G1 ($13,500) watering plants, (see image above) but the behavior appears rudimentary: the robot pours water somewhat randomly, sometimes directly onto leaves rather than soil, with visible spillage on the floor. SkildAI claims to have trained this behavior with less than one hour of human demonstration data, but has released very little footage. 1X’s Neo ($20,000, or $500/month) has shown watering capability, but the demonstration does not appear to be autonomous.

Speed is sufficient: the MindOn demonstration shows performance within 2× of human speed. However, no demonstration has shown transfer to new plant types or locations.

We classify this as “Significant limits in lab” rather than “Early research” because the basic task has been demonstrated end-to-end: picking up a watering can, going to a plant, and pouring water. The demonstrations are low quality (spillage, pouring on leaves) and show no transfer to new plants or locations, but unlike tasks such as IKEA assembly or cooking, there are no core components that remain unattempted.

3. Clean a kitchen

Significant limits in lab

Task description: The task is to autonomously clean a kitchen after a meal has been prepared, to a reasonable standard (not spotless, but visibly clean). This involves three subtasks: (1) loading dirty dishes into a dishwasher and starting a wash cycle, (2) cleaning items and storing them in cabinets and drawers, and (3) removing visible debris from cooking surfaces. The robot should use ordinary household tools like cloths, brushes, and sprays, not specialized robotic equipment.

Current capabilities: No robot can perform all three subtasks, but several have demonstrated components.

Figure has the most complete dishwasher demonstration: loading and unloading dishes, adding detergent, and starting a wash cycle. (see images below) It moves glasses, bowls, and plates between the sink, dishwasher, and cabinets. The main limitation is that it only handles larger items, not small cutlery like forks or knives. Speed is roughly 40% slower than humans. Figure has not shown transfer to new kitchens, though it has connected the OpenAI API to their robots to help them understand their progress, which may help with generalization.

Physical Intelligence has shown countertop and item cleaning: moving dirty items to the sink, cleaning a greasy pan, wiping surfaces with sponges or towels, and storing items in cabinets and drawers. (see images below) PI claims some of these demos were done in homes not present in training data, suggesting that the robot can generalize to new locations, though this is not claimed for the pan cleaning. However, transferring to new locations may be easier than handling novel object states: different dishes, varying amounts of food residue, a nearly-full dishwasher versus a nearly-empty one. These variations have not been tested.

Loki Robotics has deployed cleaning robots in campuses and corporate settings for six months and showed some dishwasher loading capability, though there is limited public data on their performance.

Other robots have shown more limited skills: SkildAI demonstrated dishwasher loading, and Sunday robot (still in alpha) showed handling cutlery, with claimed transfer to unseen houses. These robots are at least four times slower than a human. Overall, robots have shown only limited interactions with kitchen appliances beyond dishwashers, for instance closing a microwave.

We classify this as “Significant limits in lab” because while several robots have demonstrated individual subtasks, none have cleaned a full kitchen end-to-end. The dishwasher and countertop cleaning subtasks are individually approaching “Validated in lab,” but no single robot has shown integration across all three.

4. Take out the trash

Significant limits in lab

Task description: The task is to autonomously remove a trash bag from its bin, close the bag, and deposit it into an outdoor bin by navigating there. The robot must do this without breaking the bag or spilling items.

Current capabilities: Two robots have demonstrated parts of this task.

Tesla’s Optimus, a humanoid, showed picking up a trash bag, opening the lid of an outdoor bin, and dropping the bag in. However, Optimus did not remove the bag from an indoor bin or close it, and did not navigate while performing the task. The demonstration took place in a controlled training warehouse with no evidence of transfer to real environments.

Loki Robotics showed a wheeled robot (not a humanoid) taking a trash bag out of a building by navigating and using an elevator. However, the robot has only one arm and cannot close the bag itself. Loki claims to have run eight-hour shifts in campuses and corporate settings for over six months, though they note that many edge cases required teleoperation. Speed is roughly ten times slower than a human.

Neither robot has demonstrated removing a bag from an indoor bin (as opposed to just picking it up) or closing the bag. We classify this as “Significant limits in lab” rather than “Early research” because the overall task is simpler and narrower than tasks like IKEA assembly or cooking.

5. Fold basic laundry

Validated in lab

Task description: The task is to fold basic laundry items: t-shirts, towels, trousers, sheets, sweaters, and similar items. Items requiring additional manipulation before folding, such as unbuttoning a shirt, do not count as basic. The robot can be up to ten times slower than an average human. The folding need not be perfect, but should be good enough that an average person would find it satisfactory.

Current capabilities: Several robots have demonstrated laundry folding with varying degrees of reliability and generalization.

Physical Intelligence has demonstrated robots folding t-shirts, towels, and even jeans and shirts (though shirts must already be buttoned). They report 95% success on t-shirts and shorts, dropping to 75% on harder items like jeans. Figure’s humanoid robot ($130,000) has shown similar capabilities with towels. (see image above)

DYNA Robotics has the strongest evidence of sustained real-world operation. Their DYNA-1 model completed a 24-hour continuous run folding 850+ napkins at roughly 60% of human speed with a 99.4% success rate and zero human interventions. In a commercial deployment at Monster Laundry, their robot folded over 200,000 towels across 10 commercial clients in three months, with a 99% quality acceptance rate. DYNA has also demonstrated shirt folding: their improved model (DYNA-1i) folds shirts of different fabrics and sizes continuously at roughly 40 shirts per hour.

However, DYNA’s commercial deployment is limited to simple, uniform items (towels and napkins for commercial clients), not the diverse clothing items that a household robot would need to handle.

Speed varies with item complexity: simple items like towels are folded about five times slower than a human for PI and Figure, while DYNA operates at roughly 60% of human speed on napkins. Jeans are at least ten times slower for PI; folding an inside-out t-shirt takes about twenty times longer than a human.

PI has demonstrated transfer to new contexts: their π0.6 model can fold 50 novel items in a new home. DYNA has shown generalization to new environments (folding in an office lobby, a parking lot, and a conference exhibition hall), and to clothing items not encountered before7.

We classify this as “Validated in lab” because robots have demonstrated most required capabilities with reasonable reliability on simple items. DYNA’s commercial towel-folding deployment shows that sustained real-world operation is feasible for uniform items, providing evidence that deployment for more diverse laundry is within reach. But no robot has been deployed commercially for the full range of basic clothing items, and transfer to novel item types remains limited.

6. Tidy a bedroom

Validated in lab

Task description: The task is to autonomously tidy a bedroom after typical daily use so that it is orderly and safe to walk through. The robot must place loose items into appropriate locations (dirty clothes in a laundry bag, books or toys in drawers, sheets and pillows on the bed) so that main walking paths are clean. It must also make a bed that has been slept in to a reasonable standard (some unevenness is tolerated). The robot may be shown or told where categories of items belong. Cleaning (e.g. sweeping or mopping) is not in scope.

Current capabilities: Several robots have demonstrated bedroom tidying.

Physical Intelligence’s π0.5 demonstration showed the most complete capabilities: placing items in appropriate locations, putting clothes in laundry baskets, and making beds. (see images above and below) PI claims transfer to homes and items not seen in training. The model was trained on data from around 104 homes and shows performance approaching a baseline model trained directly on test environments. However, the robot often does not succeed on the first try.

Figure 03 ($130,000) is shown tidying a sofa area: moving different items including a laptop, using a bag to move toys away, and repositioning a pillow. The environment appears controlled and there is no indication of transfer to new locations or larger items.

Galaxea AI’s R1 Lite ($40,000) showed limited bed-making capabilities with 78% instruction accuracy, again in a controlled environment.

Speed is not critical for this task, but the demonstrations are slow, often shown accelerated up to 10×.

We classify this as “Validated in lab” because PI has demonstrated all subtasks with evidence of transfer to new homes and items, despite imperfect first-try reliability.

3. Navigation

Autonomous navigation is the most mature capability we cover, and the clearest near-term path to economic value. Robots that can move reliably through dangerous, remote, or otherwise hard-to-staff environments (e.g. underwater pipelines, power line inspections, last-mile delivery) are already deployed commercially. Self-driving cars are seeing widespread deployment, while warehouse robots, delivery bots, and inspection drones are starting to operate at scale. This contrasts with manipulation tasks that still largely remain in the lab.

The main reason for this is that navigation is more forgiving than manipulation. Small positioning errors rarely cause failures, there are no contact forces to manage, and simulation transfers to reality more reliably. A robot can be 10cm off when crossing a room, but not when attempting to grasp a glass.

Unlike household applications, where humanoids have the advantage of fitting in human spaces, form factors in navigation naturally specialize by terrain: wheeled robots for flat surfaces, quadrupeds for rough ground, drones for air, submersibles for water.

Tasks we assess

We selected three tasks. To different degrees, they are already seeing commercial deployment and some, like food delivery and autonomous vehicles, are expected to become huge economic markets. These tasks test the ability of robots to move reliably and safely through different environments and execute specific actions, usually transportation or video capture.

The final task, underwater navigation, serves a larger purpose, giving a sense of the remote, inaccessible and dangerous environments in which robots can operate. We briefly highlight other such contexts within that section.

Navigation: Takeaways

- Navigation capabilities are the most mature, with real-world deployment already happening at scale. Autonomous robotaxis are the poster child of this category, but there are already several commercially viable robots seeing adoption. They can reliably move and transport goods across the world and generate economic value. For now, they are working under geographical constraints and sometimes operational ones, e.g. human monitoring.

- These capabilities extend to a large number of terrains. Robots are being deployed in remote, inaccessible, and/or unsafe areas. By using specific form factors, some robots are also able to reliably move in water, underwater or in the air.

- Batteries and endurance remain a large constraint across all form factors. On land, the best quadrupeds are limited to two hours of autonomy. Wheeled robots last longer (10–20 hours) but have much more limited capabilities, e.g. they struggle on rough ground or sloped terrain. High-endurance flying and submarine drones typically max out around two hours as well.

1. Transport a human in a building

Beta/pilot deployment

Task description: The task is to autonomously transport a human to a destination in a large multi-story building such as a hospital or hotel. This requires navigating between floors (using elevators), opening doors, and locating the destination. The robot may use maps, signage, QR codes, GPS, or elevator APIs, but should not require other infrastructure installed specifically for it (such as navigation beacons).

Current capabilities: No single robot has demonstrated all required capabilities, but real-world deployments cover most of them.

WHILL’s autonomous wheelchairs ($4,000 for non-autonomous versions) transport passengers between floors at Narita Airport (see image above) using elevator integration, though the wheelchairs may follow predetermined routes rather than navigating autonomously (while still avoiding obstacles and people). Aethon’s T3 robots navigate multi-floor hospitals autonomously. Amazon’s Proteus moves loads up to 400kg in single-floor warehouses; it transports objects rather than humans, but demonstrates relevant navigation capability.

Separately, Loki Robotics, Mobile-Aloha, and Physical Intelligence have demonstrated door-opening in research settings, with Loki and Mobile-Aloha also showing elevator use. There are hints of generalization to new buildings, though evidence is limited.

Transfer to new buildings is largely untested: most deployments operate in fixed, mapped environments. Speed is limited across all systems (Proteus at roughly 4 km/h, Aethon’s T3 under 3 km/h), and Loki’s and Mobile-Aloha’s elevator interactions are at least 5× slower than a human.

We classify this as “Beta/pilot deployment” because multiple robots are operating in real-world settings with humans present (airports, hospitals). Reliability is not directly measured, but sustained deployment implies it is high. However, deployments remain geographically constrained and no single system demonstrates the full task end-to-end.

2. Deliver food

Beta/pilot deployment

Task description: The task is to autonomously deliver food from a restaurant to a customer’s location at least 500 meters away, navigating public streets or airspace. The robot may be up to 2× slower than a human delivery.

Current capabilities: Commercial food delivery by robot is already happening at limited scale. Uber Eats has deployed wheeled robots in parts of Japan for nearly two years (see image below) and plans to expand; Just Eat uses quadruped robots in the UK. Flying delivery drones are in pilot phase: Wing partners with DoorDash in Charlotte, and Zipline delivers in Dallas and Pea Ridge, Arkansas. (see image below) All deployments remain restricted to small geographic zones.

Wheeled robots operate at roughly 7 km/h while some quadrupeds can reach 15 km/h. Drone speeds are harder to assess due to regulatory limits, but they are significantly faster than ground alternatives and face fewer obstacles. Practitioners report high reliability for drones since they fly above obstacles and do not have to navigate around pedestrians or traffic. Wheeled robots are also reliable but occasionally get stuck, sometimes in the middle of the road.

We classify this as “Beta/pilot deployment” because robots are completing real deliveries to paying customers, but deployments remain restricted to small geographic zones within a handful of cities. Uber Eats’ plan to scale suggests the technology is proving viable, but broad rollout has not yet occurred.

3. Maneuver underwater

Production deployment

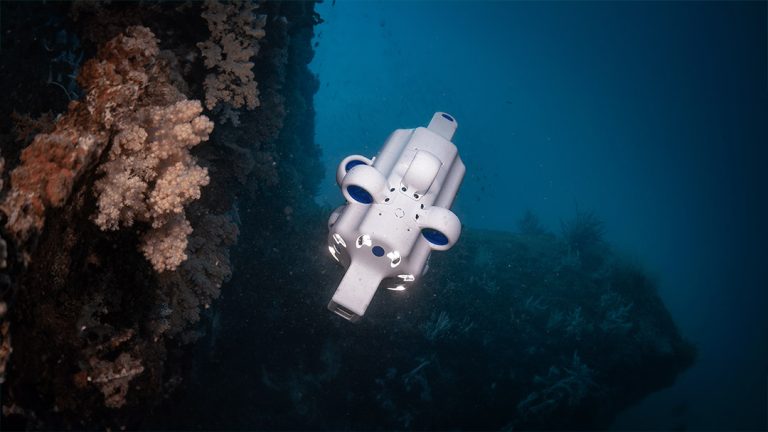

Task description: The task is to reliably and autonomously complete underwater navigation tasks such as monitoring seabeds, inspecting underwater cables, or localizing objects. The robot must operate at a depth of at least 50 meters in an uncontrolled environment. Manipulation is not required. A sufficient task is one that would otherwise require human divers or oversight, such as video capture of underwater pipes.

Current capabilities:

Several autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) perform these tasks commercially. Hydrus from Advanced Navigation (see image below) does it with a compact form factor and low price ($45,000, versus over $1 million for competitors). It operates at depths up to 300 meters with a 1.5 km range. It carries a 4K 60fps camera that tags footage with precise location data, and can complete inspections that would otherwise require divers or remotely operated vehicles. Battery life is two hours, and it moves at 1.5 knots (roughly 7 km/h).

The company reports up to 75% operational cost reduction for certain tasks. Although no official reliability figures are published, sustained commercial deployment over several years by multiple organizations implies reliability well above 99%.

We classify this as “Production deployment” because multiple AUVs are operating commercially with proven economic value.

This task was included to assess whether robots can operate in extreme or unconventional environments. Beyond underwater navigation, there are other examples of robots facing challenging conditions:

- Autonomous hauling trucks are now commonly operating in remote mining areas. Companies like Caterpillar and Komatsu have deployed thousands of vehicles working continuously with minimal human oversight. This is one of the most mature examples of autonomous heavy machinery outside controlled factory settings.

- Flyability’s Elios 3 ($29,000) is a collision-tolerant drone that can autonomously inspect spaces inaccessible or dangerous to humans: boiler interiors, cooling towers, mine shafts, and cave systems. It captures 3D scans and video while navigating environments with no GPS and limited visibility.

- Unitree demonstrated its humanoid robot walking in snow at -47°C for several hours, showing that current robots can already operate in arctic conditions.

- SkildAI’s “Skild Brain” is able to adapt to new configurations on the fly: jammed motors, shattered or missing limbs, additional parts stuck to the robot’s limbs, and unexpected forces or payloads. Google DeepMind showed similar capabilities in their Gemini Robotics 1.5 paper, where robots maintained task performance despite physical perturbations that hardcoded policies would struggle with.

- NASA’s Ingenuity helicopter completed 72 flights on Mars before its mission ended. Because signals take minutes to reach Mars, Ingenuity had to fly autonomously. NASA’s Perseverance rover similarly navigates on its own to traverse terrain and select scientific targets. These are perhaps the harshest operational environments any robot has faced: extreme temperatures, minimal atmosphere, and no possibility of physical intervention.

Looking ahead

The clearest pattern across all three domains is that autonomy works where the environment is controlled or forgiving, and struggles where it is not. Navigation succeeds even in extreme environments because small positioning errors rarely cause failures. Warehouse picking succeeds because the environment can be designed around the robot. Most household and complex manipulation tasks struggle because they demand both precision and adaptation to constantly changing settings.

Transfer is the bottleneck that separates demos from deployment. Most demonstrations show robots fine-tuned on specific tasks in specific environments. Robot foundation models are the most promising path to closing this gap: early evidence suggests that pretraining on broad data improves generalization to new objects and environments. For simpler tasks like laundry folding and tidying, there are already signs of transfer to unseen homes and novel items. For the hardest tasks in this report, reliable transfer has not yet been demonstrated.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Chris Paxton and Jeremy Collins for their useful feedback. This work was funded by a donation from Girish Sastry.

Notes

-

Market research estimates vary significantly. Sources include Mordor Intelligence ($9 billion in 2025), Fortune Business Insights ($6.5 billion in 2025), and Straits Research ($15 billion in 2024). ↩

-

Sources include Grand View Research ($34 billion in 2024) and SNS Insider ($45 billion in 2024). ↩

-

For other benchmarks and challenges to track progress on cable insertion and assembly, see the NIST Robotic Grasping and Manipulation Assembly challenge (cited in the Gemini Robotics 1.5 technical report) and the recent Manipulation-Net benchmark’s cable routing task. ↩

-

DeepMind’s robot used 2,000 demonstrations for the “easy” task with 70% success rate, 3,000 for the “messy” one with 40% success rate ↩

-

There are also reports that Tars, a Chinese robotics firm, demonstrated a robot doing embroidery, but the only evidence is commercial videos and there is very limited information about this company, so this should be treated with skepticism. ↩

-

The U.S. average cost of a professional cleaner is $175 per visit with an upper range of $750 for more than 3,000 square feet homes (tips not included). At a $20,000 price tag, an average user would recoup the cost of the robot in around two years if using these services weekly. ↩

-

Though not novel clothing types, as far as we can tell. ↩