What do “economic value” benchmarks tell us?

These benchmarks track a wide range of digital work. Progress will correlate with economic utility, but tasks are too self-contained to indicate full automation.

Published

We review three recently-developed benchmarks that aim to measure whether AI systems can perform real-world, digital, non-coding tasks of economic value: Remote Labor Index (RLI), GDPval, and APEX-Agents.

We expect progress on these benchmarks to correlate with real utility. However, the benchmark tasks are well-defined and relatively self-contained. High scores on the benchmarks, therefore, would not imply end-to-end automation of digital professions. Instead, it would imply a shift in how these jobs are done, away from manual execution and toward delegating work to AI, similar to the effect that coding agents have on software engineering today.

The benchmarks also have important differences. We give a short take-away for each.

- RLI measures AI ability to do multimedia projects that take humans several days. The first batch of evaluations likely under-elicited models, but this has been improved recently, and top scores are still very low (<5%).

- APEX-Agents measures AI ability to do tasks across classically high-paid white collar jobs that take experts a couple hours. Task instructions are self-contained, but the task environments are messier than the other two benchmarks, which probably helps with realism.

- GDPval measures AI ability to do tasks inspired by a very wide range of economically valuable digital work. Tasks take professionals about a day to complete. Realism is doubly limited by the tasks being self-contained and there being no messy environment to navigate. This is also the closest of these benchmarks to being saturated.

The rest of the article goes into greater detail.

| Facet | RLI | APEX-Agents | GDPval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developer / Evaluator | CAIS + Scale AI | Mercor | OpenAI |

| # of Tasks | 240 (10 public) | 480 (all public) | 1320 (220 public) |

| Content Area | Tasks with visual outputs (web design, product art, video editing, etc.) | Investment banking, management consulting, corporate law | Tasks from 44 occupations, mostly research and writing |

| Task Provenance | Real freelance projects | Devised by experts, optimized to be hard for models | Devised by experts |

| Information Provided in Task | Only necessary information | Much more information than necessary | Only necessary information |

| Human Time (avg) | 29 hours | 2 hours | 7 hours |

| Evaluation has web access? | Yes | No | Yes |

| Evaluation Method | Expert judgment of human vs. AI output | AI judgment vs. rubric | Expert judgment of human vs. AI output |

| Top scores as of Feb '26 | 4% | 30% | 74% |

Example tasks

Below we give three highly summarized task descriptions from each benchmark. These summaries don’t convey the full detail of the task specifications or the complexity of relevant materials, but we find them helpful as a reference.

RLI

- Create a 3D model and five product feature animations for a set of earbuds. The provided materials consist of images of the earbuds from different angles.

- Make a custom arrangement with a specific list of instruments for the song Singing in the Rain. A link to a YouTube video with audio of the song is provided.

- Render various interior design options for an apartment. The provided materials include multiple images of the floor plans and the existing interior.

APEX-Agents

- Model the net-present value of shareholder distributions if a given company converts to a REIT. The file system contains relevant documents about the given company, as well as an Excel sheet for calculations. It also contains files pertaining to unrelated companies and projects.

- Determine whether the data exposed in a given data breach is personal data under GDPR. The file system contains information about the specific breach as well as articles about GDPR. It also contains files related to an unrelated client and other, non-EU privacy laws.

- Analyze which employees at a food manufacturer are most ready to take a digital training program. The file system contains information about the employees at the company, as well as other company-related information and unrelated projects.

GDPval

- As an account manager at a medical equipment manufacturer, provide a quote to a prospective client. In addition to the request for the quote, an Excel sheet with pricing information is provided. The quote must adhere to certain WHO standards, which are expected to be found via web search. The intended output is an Excel file.

- As a supervisor at a private investigation firm, compile a report regarding an insurance claim. Two reports by field investigators, as well as AI-generated images, are provided. The intended output is a PDF.

- As a service rep at a government agency, respond to an inquiry about a Thrift Savings Plan. Information about the plan is expected to be found via web search, and the deliverable is the text of an email.

Tasks are sourced in different ways, from different fields

We give an overview of the sourcing and structure of each benchmark’s tasks. One major difference is that RLI tasks are from real-world projects, whereas APEX-Agents and GDPval tasks are devised by experts. This gives RLI an edge in task realism. RLI also differs notably in output format: its tasks mostly ask for multimedia output, as opposed to the research-oriented tasks of the other two, whose outputs are typically text or Microsoft Office files.

RLI tasks are real projects previously completed by freelancers on the platform Upwork.1 Perhaps the most notable selection criterion is that project output must be possible to evaluate visually.2 This is why the benchmark skews toward multimedia work.

An RLI task package consists of:

- A prompt, derived from the original client’s project brief

- Input files such as audio and images

- The freelancer’s actual deliverable, used in grading

Output files are rendered in a web viewer for human raters to inspect.

Tasks were assembled by freelancers. They were reviewed to ensure that instructions and materials were complete, as well as appropriately anonymized.

APEX-Agents tasks are sourced from scratch, created by real professionals in three roles: investment banking analyst, management consultant, and corporate lawyer.

An APEX-Agents task package consists of:

- A prompt

- An environment with files and applications, mimicking a real-world setup. The environments typically contain many files and applications that are irrelevant for performing the task.

- A grading rubric

Output typically consists of a text response (≈90% of tasks) or the creation of a file.

Tasks were created by professionals and underwent multiple rounds of reviews, including LLM-based refinements to make the tasks harder. It’s unclear to what extent this made the task distribution unrepresentative compared to actual work.

GDPval aimed to source tasks to cover a large breadth of economic activity. Starting with the nine industries that contributed the most to US GDP, 44 occupations were identified where a substantial amount of work is performed digitally.3 For each occupation, 30 tasks were created by human experts.

A GDPval task package consists of:

- A prompt

- (Optionally) reference files

Output consists of various files, typically Microsoft Office standards.

Tasks were created by teams of experts, with five contributors per task on average, and underwent multiple rounds of review by humans and LLMs. This included at least a basic filter for task complexity, e.g. that tasks should seem to require substantially more than five minutes of work.

Finally, a note on how task creators were compensated. In the case of RLI, freelancers were paid an average of $41 to provide an old work sample. We don’t know how task creators were compensated for APEX-Agents or GDPval. While the public samples from all three benchmarks generally look reasonable to us, we don’t know what nuance may be missing due to task creators being inadequately incentivized to create realistic tasks.

Lack of interaction and environment messiness affect task realism

All three benchmarks consist of one-shot interactions. That is, on the basis of a single, static prompt, an AI system goes off and works, and then produces a single set of outputs to be graded. Naturally, this is different from human workflows which often involve extended back-and-forths to elicit goals, specify requirements, and give feedback.

GDPval and RLI both provide all relevant information in the form of the task specification prompt and any necessary input files. This is a substantially cleaner setup than a typical office work context, where an employee uses a computer to interact with multiple applications and systems, managing many files and tasks at once. RLI tasks are similarly clean, but this seems more realistic for freelancing work where projects naturally have much less context.

APEX-Agents attempts to address this aspect of realism by providing environments with an intentionally messy filesystem, including duplicate files and half-finished projects unrelated to the given task. We can’t say how realistic this constructed messiness is, but we suspect it makes RLI a better measurement of the ability of AI systems to “drop into” unfamiliar contexts.

That said, tasks in all the benchmarks are performed in isolation from any broader business context, such as a company’s general policies, processes, or strategy that workers may have to be mindful of. Data is also cleaned of proprietary or personally identifiable information, which may have a tendency to simplify it.

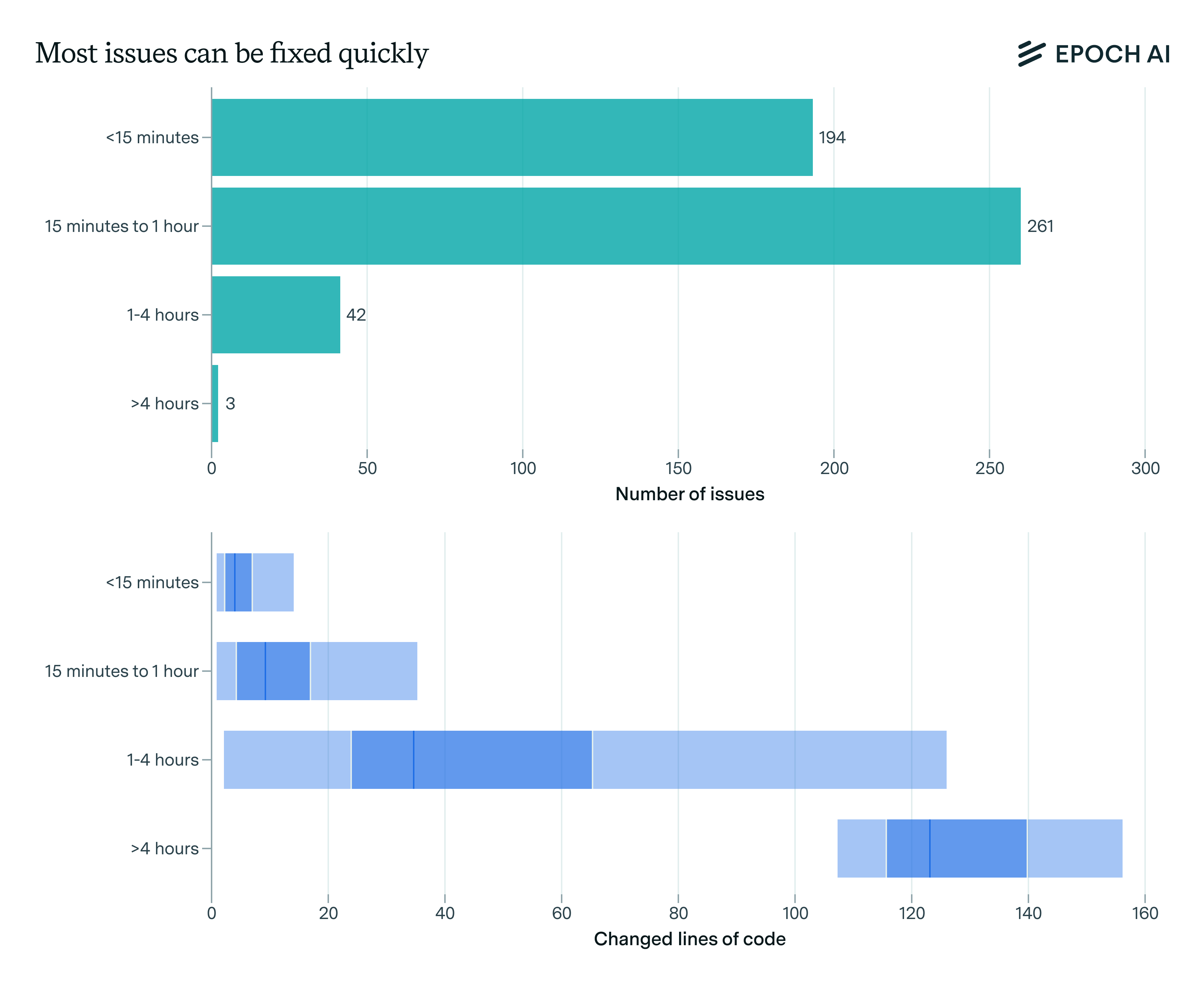

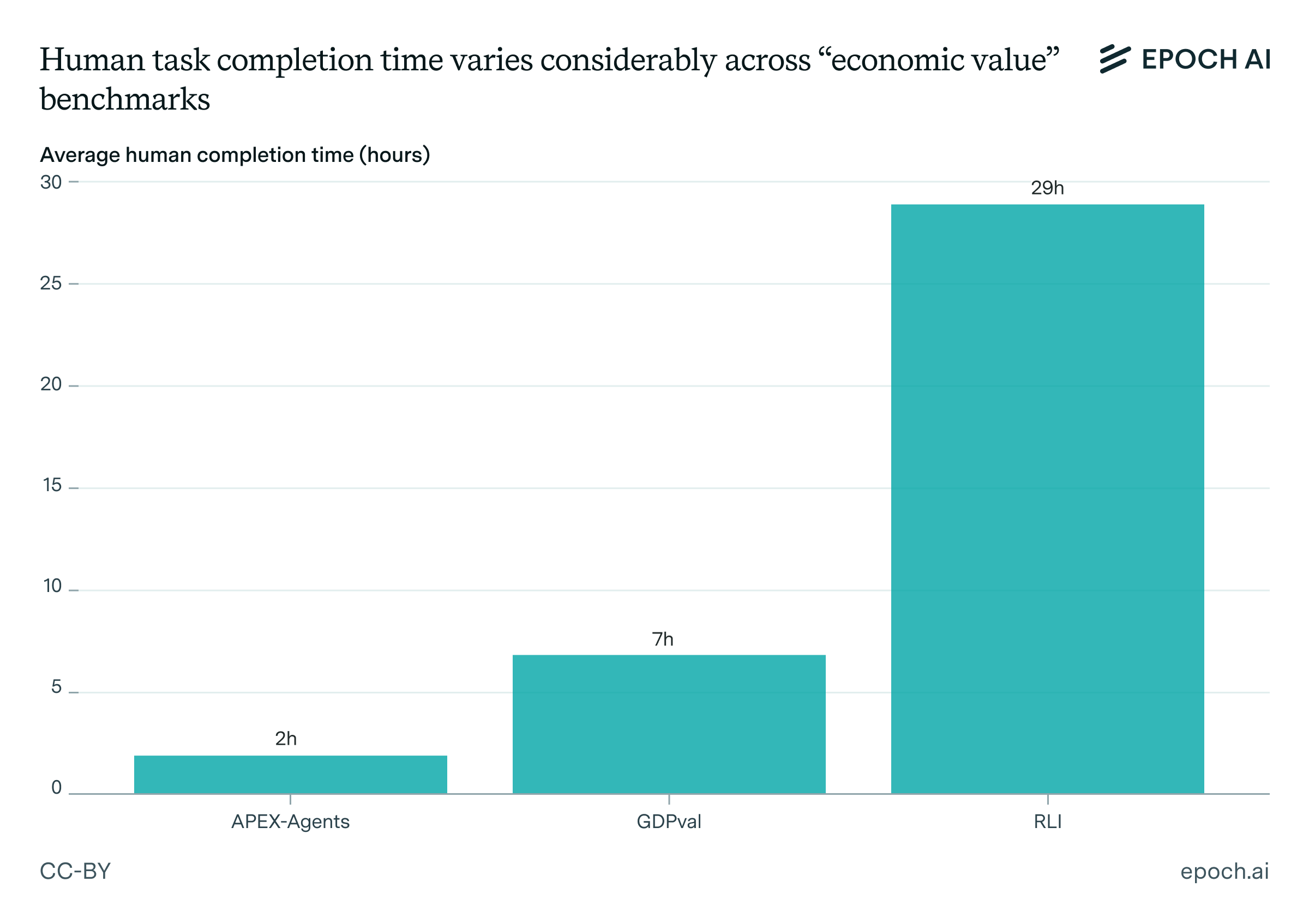

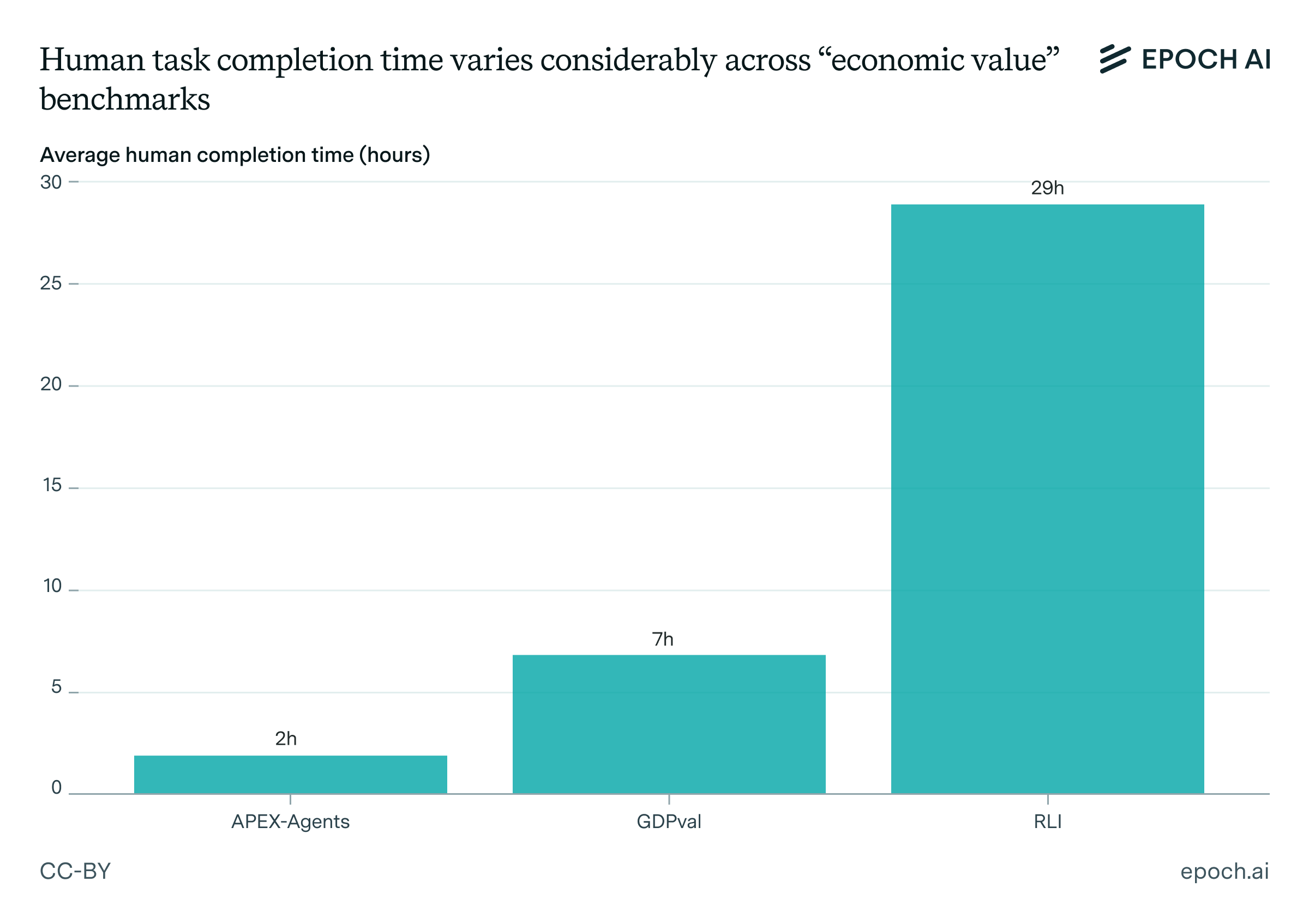

Estimated human time-to-complete varies substantially

GDPval estimated average task completion time by having experts complete the tasks. APEX-Agents was similar, though only a subsample of tasks were completed by experts. The average completion time for these two was 7 and 2 hours, respectively.

RLI asked freelancers to report the hours they spent on the task. The average reported time was 29 hours. While such self-reported data may be biased, the completion time data does correlate well with the wages the freelancers were paid for the work, suggesting it is somewhat realistic.

What accounts for these longer completion times? We only have the public set of 10 tasks to go on, but the gist seems to be that multimedia tasks in RLI simply involve a lot of fiddly details that humans do indeed need time to complete. The task of creating a 3D model and five product feature animations for a set of earbuds is one of the longest, reported at 60 hours. Making a custom arrangement for the song Singing in the Rain is about average, taking 30 hours. The task of making interior design renderings for an apartment, also the most expensive of the public set, is reported at 22 hours.

It’s plausible that the economic value of the tasks is more similar than their time horizons. For RLI, projects were billed to the original clients for an average of $600. For, say, APEX-Agents, two hours of an experienced corporate lawyer’s time could exceed that cost.

Web access makes evaluation a bit less reliable for GDPval

While APEX-Agents is run without web access, both RLI and GDPval allow the agents to browse the web. Since RLI tasks were initially done as real-world work, some of the task outputs are sometimes available online. RLI maintains a blocklist for such cases.4 Beyond this, as benchmark samples are not public, and most do not seem to rely on highly specific information on the web, the overall impact of solutions being available online should be relatively small.

However, over half of GDPval tasks are research-based and rely more fundamentally on live web access. We observe two issues with this design. First, some tasks require the use of web sources that might become inaccessible as websites change over time. This currently affects only two samples5, though we expect it to increase over time. Second, about 5% of tasks assume a point of view that is now in the past. One task, for example, asks prospectively for “a comprehensive analysis of the energy market […] for the first half (H1) of 2025”. It seems plausible that models will find this task easier to perform in hindsight, where relevant information — including the actual events of the given period — is much more readily available.

Evaluation strategies differ substantially

In GDPval, expert humans compare the reference human work product to the AI output, selecting which they prefer, including a “tie” option. RLI is similar, asking experts if the AI output is “at least as good as” the reference output. In the original papers, GDPval uses at least two human judges, and RLI uses three. It is not stated how many judges are used in subsequent evaluations.

GDPval reports “tie” rates separate from “win” rates, though the ceiling on win rates is unclear: for some tasks there may not be much room to improve on the human reference output. We thus tend to consider the win+tie rates as most informative. This is also most directly comparable to RLI.

Head-to-head comparison is intuitive for assessing whether AI systems are producing output on par with humans. That said, we don’t know much about how these comparisons are performed. In particular, we don’t know what is done to facilitate experts adopting the perspective of an economically-motivated customer vs. judging output only on superficial characteristics.6

APEX-Agents uses a rubric with self-contained facts that are checked by an LLM for correctness. This is a common technique for evaluating output in facts-based benchmarks. The relatively objective nature of the APEX-Agents rubrics make this seem reasonable in this case as well.

Models have made different amounts of progress on the benchmarks

As of this writing, the top score on GDPval is a 74% win+tie rate (60% win + 14% tie), achieved by GPT-5.2 Pro, with GPT-5.2 (xhigh) scoring 71% (50% win + 21% tie). Furthermore, Artificial Analysis’s third-party implementation of GDPval shows Opus 4.6 as substantially outperforming GPT-5.2 (xhigh), suggesting it might score even higher than 74% on an official OpenAI evaluation.7 GDPval is the closest of the three to being saturated.

The top score on RLI, by comparison, is 4% from Opus 4.6. This is not so surprising, given both the longer human completion times associated with the tasks and a general, field-wide weakness at multimodal tasks vs. text-only tasks. It seems reasonable to expect this benchmark to take the longest to saturate, though see below for discussion about whether these results under-elicit model performance.

APEX-Agents is in between, with Opus 4.6 achieving the current top score of 30%.

The chosen scaffolds may under-elicit capabilities

All of these benchmarks run on agentic scaffolds, meaning the AI system iteratively interacts with an environment to produce the final output. As we have written before, the implementation details of scaffolds can make large differences in performance.

RLI uses different scaffolds depending on the models’ capabilities, including integrated agent products like Manus, a computer-use agent (CUA) scaffold developed by Scale AI and CAIS based on an Ubuntu desktop with various standard tools, and a CLI environment based on the OpenHands CLI with API access to various multimodal models for images, videos, and voice.

RLI tasks require models to create various kinds of output files, including Autodesk/CAD, Photoshop files, or 3D models. None of the scaffolds used are particularly good fits for this. In the Ubuntu-based CUA scaffold, popular applications like Photoshop or Fusion360 won’t work due to lacking Linux support, so models must fall back to less capable alternatives like GIMP or FreeCAD. The CLI scaffold, on the other hand, privileges the multimodal tools it specifically includes, strongly encouraging models to rely on those tools. In practice, for instance, this means that Veo 3 Preview is used to generate videos, and thus the model being assessed inherits Veo’s weaknesses, such as inaccurately rendering text.

The original set of evaluations for RLI with these two scaffolds may have been especially problematic. Models were given a one-hour total time limit, and the environments did not come with much relevant software preinstalled. However, the CAIS and Scale AI team conveyed to us that they made significant upgrades to the in-house scaffolds, including an increased suite of pre-installed software and a considerably extended per-task time limit. These improvements were in place for the Opus 4.5 evaluation, where it scored only 4%.

APEX-Agents uses a custom scaffold based on a simple ReAct loop with 79 tools, which range from listing files to code execution or editing the footer in a document. These tools are managed by the model, i.e., the model can add (or remove) them from the context.

We suspect under-elicitation is a problem here as well. Many of the 79 tools do nothing more than wrap well-known Python tools such as python-docx or python-pptx. The models are likely more capable of using these tools directly, compared to having to learn the wrappers’ new syntax. This is also a large number of tools and the agent is tasked with the management of the tools itself, which adds complexity. We suspect that coding-only scaffolds such as Claude Code would perform better.

GDPval evaluates OpenAI models with the web search and code interpreter tools with various libraries installed, comparable to ChatGPT. Claude models were evaluated using the Web UI (i.e., claude.ai). Matching the experience of web app users seems reasonable, though it again seems possible for other scaffolds, e.g. Codex or Claude Code, to perform better. No details were given for how Gemini or Grok models were evaluated. The third-party implementation GDPval-AA uses the same custom scaffold across all models.

Conclusion

These benchmarks measure performance on isolated tasks that require a wide range of human expertise and take humans several hours to several days. We believe these are useful instruments, though, to be fair, they don’t live up to their names: there is far more “remote labor” than represented in RLI, and many more sources of GDP than captured by GDPval.

A suitable comparison might be SWE-bench Verified. These benchmarks capture a narrow slice of the relevant jobs, but not the full thing.

Saturation on these benchmarks would still transform day-to-day work, even if it does not replace it. The professions would see a relative speedup in some parts of their work similar to what programmers have witnessed in the past few months. The execution of tasks accelerates, while planning and delegation become an increasing share of a human’s time. Verification also becomes critical, with workers spending relatively more of their time checking the correctness of AI output.

We expect progress on these benchmarks to correlate with real utility of AI systems, but more as assistants for performing isolated tasks than drop-in replacements for entire jobs. Pushing further in that direction would require benchmarks that tackle more complete end-to-end tasks situated in the messy context of real work.

Notes

-

All freelancers had at least 2,000 hours and $23,000 earnings on Upwork at the time they completed the projects used in RLI. ↩

-

And/or aurally. ↩

-

These occupations come from a wide range of industries, including healthcare, manufacturing, and real estate. Judgments about how much work is performed digitally were made using statistics from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, whose O*NET resource includes granular data on what tasks are performed in various occupations. An LLM is used to judge which of these tasks are primarily physical vs. digital. ↩

-

However, blocklists are not a silver bullet, as archives or other third-party sites may re-host the same content. ↩

-

This was determined by extracting the links from all public samples and testing them with curl. Samples with issues: 1, 2. Of course this does not test whether the necessary information is still available, even if the links do work. ↩

-

The RLI methodology only states, “In all evaluations, we instruct evaluators to adopt the perspective of a reasonable client to minimize subjectivity.” ↩

-

Using only the public tasks, GDPval-AA reports Elo scores for models, using Gemini 3 Pro to judge model outputs head to head. They do not use human outputs and thus cannot give an absolute win+tie score. ↩